One of the major issues regarding the modern corporation is how individual department heads operate. The focus is on how, when they are in an autonomous or semi-autonomous role, they may take advantage of that position to either consciously or subconsciously negatively affect organisational performance. There are a number of ways that department heads position may do this. The first is competition. Individual department heads, infused with the idea that their department is the most important and the best, may compete with other for resources and money within the organisation. Secondly there is the concept of bounded rationality, which means that department heads, only having full knowledge of their own organisational remits, make decisions from a limited perspective. Thus a department head may make a decision that affects another department in ways that his limited level of knowledge about that department cannot predict. Thirdly there is principal-agent problems. Basically, directors of a company can find it hard, impossible even, to contradict a department head's recommendation or decision because their knowledge of what goes on a department is vastly inferior to his. This is a problem exacerbated by the fact that the department heads is the one who provides them with the information about the department in question. Lastly, and I imagine this goes without saying, personality plays a role, in ways that our own experiences of work can help us to imagine. Overall these issues pose problems for organisations as department heads, in their capacity as decision makers, can potentially neglect the overall performance of the organisation in favour of their department's own efficiency.

Naturally these problems were encountered in Victorian railway companies. Indeed Bonavia, in his overview of the structure of Nineteenth Century railway companies in The Organisation of British Railways, hints that the conflicts that were engaged between departments, mostly including the Superintendent of the Line and the Locomotive Superintendents. The Superintendent of the Line, who's main job was to monitor the trains while they were out on the line, had to have at their disposal enough locomotives to keep the trains to timetable. The Locomotive Superintendent, who usually also had responsibility for the locomotive works which built and maintained the rolling stock, had to make sure the staff there had a steady flow work and that costs were kept at a constant level. Therefore the two department heads may bash their heads together on exactly where locomotives were going to be at any given time. This is only one example of inter-departmental conflict, and shows the sort of issues that might arise. Overall there many department heads within the Victorian railway industry that had reputations that were less than favourable because of their actions.

Naturally these problems were encountered in Victorian railway companies. Indeed Bonavia, in his overview of the structure of Nineteenth Century railway companies in The Organisation of British Railways, hints that the conflicts that were engaged between departments, mostly including the Superintendent of the Line and the Locomotive Superintendents. The Superintendent of the Line, who's main job was to monitor the trains while they were out on the line, had to have at their disposal enough locomotives to keep the trains to timetable. The Locomotive Superintendent, who usually also had responsibility for the locomotive works which built and maintained the rolling stock, had to make sure the staff there had a steady flow work and that costs were kept at a constant level. Therefore the two department heads may bash their heads together on exactly where locomotives were going to be at any given time. This is only one example of inter-departmental conflict, and shows the sort of issues that might arise. Overall there many department heads within the Victorian railway industry that had reputations that were less than favourable because of their actions.Within the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) one man exemplified the problematic department head. That man was Dugald Drummond, the company's Locomotive superintendent between 1895 and 1912. Drummond had been born in 1840 to George Drummond who worked on the permanent way on the Ardrossan Railway in Ayrshire, Scotland. After doing his apprenticeship he gradually working his way up through various grades on various railways, eventually becoming Locomotive Superintendent on the North British Railway in 1875. He then moved to the Caledonian Railway in 1882, and stayed until 1890 when he became moved to Australia to take charge of the Australasian Locomotive Engine Works. After the scheme failed he started the moderately successful Glasgow Railway Engineering Company. In 1895 he was offered the job at the L&SWR, at a salary much less than he was paid on the Caledonian railway. As a result this move began one of the most interesting periods in the history of the L&SWR's Senior Management.

Drummond at the outset was given a very free hand by the company's General Manager, Charles Scotter. The engineer used this delegated power to firstly shake up the Locomotive Works, which had previously been under the charge of Mr W.F. Pettigrew. Prior to Drummond's appointment the, Locomotive Superintendent, William Adams, was suffering from failing memory and vagueness and Pettigrew was forced to paper over the gaps in Adams' work. This had meant that the works had fallen behind schedule and repairs were undertaken slowly. As a result, and using his devolved control, Drummond brought in his chief draughtsman from the Caledonian Railway's works at St Rollox, William Urie. Drummond also instigated weekly meetings to check the progress of all locomotives under repair and construction, and another to report on the mishaps of drivers when handling trains. Within months of his appointment repair and construction was ahead of schedule and by 1896 the Nine Elms works were operating at full capacity. He also came down hard on drivers caught drinking on duty, was in closer contact with the staff and was approachable to be the arbiter of disputes and disagreements.

These were all positive features of Drummond's tenure as locomotive superintendent, however he also was a prime exemplar of a department head that focussed on his own affairs to the detriment of the company as a whole. Firstly this was illustrated through the 'bug' (shown).

Built in 1899 this small 2-4-2 locomotive with a saloon at the back, was a private vehicle so that Drummond could move around the network when and if he pleased. The 'Bug,' apart from ferrying Drummond to and from work, had a habit of turning up next to drivers waiting at signals. If excess steam was detected the driver would be chastised across the gap by Drummond (who himself was a consummate driver.) The driver would then receive a notice the following day to see Drummond in his office The 'Bug' would also enable Drummond to turn up unannounced at the most remote engine sheds for an inspection. Further Drummond's frequent inspection runs would take no notice of the traffic timetable, much to the discontent of passengers. Overall its approach would alarm staff bringing with it, 'foreboding and trouble.'

Built in 1899 this small 2-4-2 locomotive with a saloon at the back, was a private vehicle so that Drummond could move around the network when and if he pleased. The 'Bug,' apart from ferrying Drummond to and from work, had a habit of turning up next to drivers waiting at signals. If excess steam was detected the driver would be chastised across the gap by Drummond (who himself was a consummate driver.) The driver would then receive a notice the following day to see Drummond in his office The 'Bug' would also enable Drummond to turn up unannounced at the most remote engine sheds for an inspection. Further Drummond's frequent inspection runs would take no notice of the traffic timetable, much to the discontent of passengers. Overall its approach would alarm staff bringing with it, 'foreboding and trouble.'The 'Bug' was symptomatic of Drummond's centralisation of the Locomotive department on him. There was not one aspect of Locomotive Department operation that did he did not know about, or had the ability to pass judgement on. In addition he created a situation whereby he was a very important presence within the company and the first Locomotive Superintendent that did things truly 'his way'. Compared with Adams, Drummond consulted the Locomotive Committee far less and took more actions by himself without their consent. As far as can be detected neither Scotter, not his successor Charles Owens, nor the Locomotive Committee (made up of directors) tried to force him to change or be subservient to them. It also meant that Drummond's suggestions when it came to major investment were endorsed far more readily by directors because of his unique and intimate understanding of the department. In 1898 the decision to move the Locomotive Works to Eastleigh was heavily influenced by Drummond. Where previously these types of decisions would have been made by a special committee or the board of directors, in this case the decision was made very quickly at the board's Locomotive sub-committee.

Drummond was certainly an autocrat in the Locomotive Department. Bonavia's argument that there were conflicts between the Locomotive Superintendent and other senior managers seems unfounded in the case of Drummond up to 1912. There seemed not to be one man in the company, neither director, nor manager, that felt confident enough to take him on. However 1912 was the year of changes. The directors brought in a new general manager, Herbert Ashcombe Walker, who was charged with reforming the company. It was at this point that the only case of conflict with another senior manager has been documented.

Walker tried to assert his authority over Drummond before the engineer's death in September 1912 and Urie's son remembered an early spat between them. During the 1911-12 coal strike Walker ordered some American coal without consulting Drummond. Angered by this, Drummond had a bucket of the coal brought to Waterloo and emptied the contents over Walker's officer floor. Walker however was not going to put up with this sort of insubordination, and on the death of Drummond, Urie was appointed Locomotive Engineer. Urie informed Walker that he had never expected to get the job at the age of 59. Walker told him not to worry, he was going to fire Drummond very soon anyway. After his death, obviously trying to assert his control over the Locomotive Department, on the advice of Walker, the Board made Urie Locomotive Engineer rather than Chief Mechanical engineer. In addition the role of running the trains, which for many years had been under the Chief Mechanical Engineers' Department, was transferred to the Traffic Department.

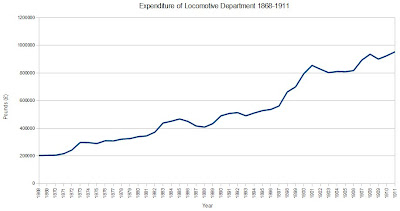

Overall there is evidence that Drummond was a typical isolated department head that got his own way and perused his own interests within the department. The way he ran his department, using large amounts of resources and at time building locomotives that were simply 'flights of fancy,' must have affected the costs that the department accrued. Table 1 clearly indicates that after 1895, the year of Drummond's appointment, the costs of running the Locomotive Department rose significantly. Of course other factors may have played a role in the increase, such as the costs required to make the department efficient or bring the locomotive stock up to the required quality given Adams' ailing last years. However, what is clear is that ever since 1868 department costs had risen at a steady rate and after 1895 there was a significant increase. Thus, Drummond's influence and independence did have a detrimental affect on overall company efficiency.

Sources:

Sources:Urie, J.C. 'Tips for aspiring CME's' South Western Circular, Vol.10 No. 9, (January, 1997) pp.221

'Dugald Drummond Obituary', The Railway Engineer, December 1912, reprinted in The South Western Circular, Vol. 8 No. 6 (April 1990), pp.145

Chacksfield, J.E. The Drummond Brothers, (Ringwood, 2005)

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar