On the death of William in 1837[11] Jane, received £5000, which would have passed to Cornelius because of wives’ property rights in the period.[12] I am not one hundred per cent sure what happened next, however, my best theory is that in late 1837 Cornelius set up a coaching business on his own, probably using this money. [13] However, he did not inherit any of William’s business directly, as most of it was taken over by his son, Thomas.[14] Yet, he clearly had some use of the Hen and Chickens Inn site, as shown by the following advert from The Liverpool Mercury on 7 December; ‘Royal Mails and Fast Post Coaches leave the above Establishment (Hen and Chickens Coach Office, New Street Birmingham), to all parts of the Kingdom, immediately upon the arrival of the different Railway Trains.’ The advert was signed ‘Cornelius Stovin and Co. Proprietors.’[15]

On the death of William in 1837[11] Jane, received £5000, which would have passed to Cornelius because of wives’ property rights in the period.[12] I am not one hundred per cent sure what happened next, however, my best theory is that in late 1837 Cornelius set up a coaching business on his own, probably using this money. [13] However, he did not inherit any of William’s business directly, as most of it was taken over by his son, Thomas.[14] Yet, he clearly had some use of the Hen and Chickens Inn site, as shown by the following advert from The Liverpool Mercury on 7 December; ‘Royal Mails and Fast Post Coaches leave the above Establishment (Hen and Chickens Coach Office, New Street Birmingham), to all parts of the Kingdom, immediately upon the arrival of the different Railway Trains.’ The advert was signed ‘Cornelius Stovin and Co. Proprietors.’[15] Minggu, 18 Maret 2012

An Early Railway Manager - A Perpetual Failure

On the death of William in 1837[11] Jane, received £5000, which would have passed to Cornelius because of wives’ property rights in the period.[12] I am not one hundred per cent sure what happened next, however, my best theory is that in late 1837 Cornelius set up a coaching business on his own, probably using this money. [13] However, he did not inherit any of William’s business directly, as most of it was taken over by his son, Thomas.[14] Yet, he clearly had some use of the Hen and Chickens Inn site, as shown by the following advert from The Liverpool Mercury on 7 December; ‘Royal Mails and Fast Post Coaches leave the above Establishment (Hen and Chickens Coach Office, New Street Birmingham), to all parts of the Kingdom, immediately upon the arrival of the different Railway Trains.’ The advert was signed ‘Cornelius Stovin and Co. Proprietors.’[15]

On the death of William in 1837[11] Jane, received £5000, which would have passed to Cornelius because of wives’ property rights in the period.[12] I am not one hundred per cent sure what happened next, however, my best theory is that in late 1837 Cornelius set up a coaching business on his own, probably using this money. [13] However, he did not inherit any of William’s business directly, as most of it was taken over by his son, Thomas.[14] Yet, he clearly had some use of the Hen and Chickens Inn site, as shown by the following advert from The Liverpool Mercury on 7 December; ‘Royal Mails and Fast Post Coaches leave the above Establishment (Hen and Chickens Coach Office, New Street Birmingham), to all parts of the Kingdom, immediately upon the arrival of the different Railway Trains.’ The advert was signed ‘Cornelius Stovin and Co. Proprietors.’[15] Senin, 29 Maret 2010

Dugald Drummond - The South Western's detrimental manager

One of the major issues regarding the modern corporation is how individual department heads operate. The focus is on how, when they are in an autonomous or semi-autonomous role, they may take advantage of that position to either consciously or subconsciously negatively affect organisational performance. There are a number of ways that department heads position may do this. The first is competition. Individual department heads, infused with the idea that their department is the most important and the best, may compete with other for resources and money within the organisation. Secondly there is the concept of bounded rationality, which means that department heads, only having full knowledge of their own organisational remits, make decisions from a limited perspective. Thus a department head may make a decision that affects another department in ways that his limited level of knowledge about that department cannot predict. Thirdly there is principal-agent problems. Basically, directors of a company can find it hard, impossible even, to contradict a department head's recommendation or decision because their knowledge of what goes on a department is vastly inferior to his. This is a problem exacerbated by the fact that the department heads is the one who provides them with the information about the department in question. Lastly, and I imagine this goes without saying, personality plays a role, in ways that our own experiences of work can help us to imagine. Overall these issues pose problems for organisations as department heads, in their capacity as decision makers, can potentially neglect the overall performance of the organisation in favour of their department's own efficiency.

Naturally these problems were encountered in Victorian railway companies. Indeed Bonavia, in his overview of the structure of Nineteenth Century railway companies in The Organisation of British Railways, hints that the conflicts that were engaged between departments, mostly including the Superintendent of the Line and the Locomotive Superintendents. The Superintendent of the Line, who's main job was to monitor the trains while they were out on the line, had to have at their disposal enough locomotives to keep the trains to timetable. The Locomotive Superintendent, who usually also had responsibility for the locomotive works which built and maintained the rolling stock, had to make sure the staff there had a steady flow work and that costs were kept at a constant level. Therefore the two department heads may bash their heads together on exactly where locomotives were going to be at any given time. This is only one example of inter-departmental conflict, and shows the sort of issues that might arise. Overall there many department heads within the Victorian railway industry that had reputations that were less than favourable because of their actions.

Naturally these problems were encountered in Victorian railway companies. Indeed Bonavia, in his overview of the structure of Nineteenth Century railway companies in The Organisation of British Railways, hints that the conflicts that were engaged between departments, mostly including the Superintendent of the Line and the Locomotive Superintendents. The Superintendent of the Line, who's main job was to monitor the trains while they were out on the line, had to have at their disposal enough locomotives to keep the trains to timetable. The Locomotive Superintendent, who usually also had responsibility for the locomotive works which built and maintained the rolling stock, had to make sure the staff there had a steady flow work and that costs were kept at a constant level. Therefore the two department heads may bash their heads together on exactly where locomotives were going to be at any given time. This is only one example of inter-departmental conflict, and shows the sort of issues that might arise. Overall there many department heads within the Victorian railway industry that had reputations that were less than favourable because of their actions.Within the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) one man exemplified the problematic department head. That man was Dugald Drummond, the company's Locomotive superintendent between 1895 and 1912. Drummond had been born in 1840 to George Drummond who worked on the permanent way on the Ardrossan Railway in Ayrshire, Scotland. After doing his apprenticeship he gradually working his way up through various grades on various railways, eventually becoming Locomotive Superintendent on the North British Railway in 1875. He then moved to the Caledonian Railway in 1882, and stayed until 1890 when he became moved to Australia to take charge of the Australasian Locomotive Engine Works. After the scheme failed he started the moderately successful Glasgow Railway Engineering Company. In 1895 he was offered the job at the L&SWR, at a salary much less than he was paid on the Caledonian railway. As a result this move began one of the most interesting periods in the history of the L&SWR's Senior Management.

Drummond at the outset was given a very free hand by the company's General Manager, Charles Scotter. The engineer used this delegated power to firstly shake up the Locomotive Works, which had previously been under the charge of Mr W.F. Pettigrew. Prior to Drummond's appointment the, Locomotive Superintendent, William Adams, was suffering from failing memory and vagueness and Pettigrew was forced to paper over the gaps in Adams' work. This had meant that the works had fallen behind schedule and repairs were undertaken slowly. As a result, and using his devolved control, Drummond brought in his chief draughtsman from the Caledonian Railway's works at St Rollox, William Urie. Drummond also instigated weekly meetings to check the progress of all locomotives under repair and construction, and another to report on the mishaps of drivers when handling trains. Within months of his appointment repair and construction was ahead of schedule and by 1896 the Nine Elms works were operating at full capacity. He also came down hard on drivers caught drinking on duty, was in closer contact with the staff and was approachable to be the arbiter of disputes and disagreements.

These were all positive features of Drummond's tenure as locomotive superintendent, however he also was a prime exemplar of a department head that focussed on his own affairs to the detriment of the company as a whole. Firstly this was illustrated through the 'bug' (shown).

Built in 1899 this small 2-4-2 locomotive with a saloon at the back, was a private vehicle so that Drummond could move around the network when and if he pleased. The 'Bug,' apart from ferrying Drummond to and from work, had a habit of turning up next to drivers waiting at signals. If excess steam was detected the driver would be chastised across the gap by Drummond (who himself was a consummate driver.) The driver would then receive a notice the following day to see Drummond in his office The 'Bug' would also enable Drummond to turn up unannounced at the most remote engine sheds for an inspection. Further Drummond's frequent inspection runs would take no notice of the traffic timetable, much to the discontent of passengers. Overall its approach would alarm staff bringing with it, 'foreboding and trouble.'

Built in 1899 this small 2-4-2 locomotive with a saloon at the back, was a private vehicle so that Drummond could move around the network when and if he pleased. The 'Bug,' apart from ferrying Drummond to and from work, had a habit of turning up next to drivers waiting at signals. If excess steam was detected the driver would be chastised across the gap by Drummond (who himself was a consummate driver.) The driver would then receive a notice the following day to see Drummond in his office The 'Bug' would also enable Drummond to turn up unannounced at the most remote engine sheds for an inspection. Further Drummond's frequent inspection runs would take no notice of the traffic timetable, much to the discontent of passengers. Overall its approach would alarm staff bringing with it, 'foreboding and trouble.'The 'Bug' was symptomatic of Drummond's centralisation of the Locomotive department on him. There was not one aspect of Locomotive Department operation that did he did not know about, or had the ability to pass judgement on. In addition he created a situation whereby he was a very important presence within the company and the first Locomotive Superintendent that did things truly 'his way'. Compared with Adams, Drummond consulted the Locomotive Committee far less and took more actions by himself without their consent. As far as can be detected neither Scotter, not his successor Charles Owens, nor the Locomotive Committee (made up of directors) tried to force him to change or be subservient to them. It also meant that Drummond's suggestions when it came to major investment were endorsed far more readily by directors because of his unique and intimate understanding of the department. In 1898 the decision to move the Locomotive Works to Eastleigh was heavily influenced by Drummond. Where previously these types of decisions would have been made by a special committee or the board of directors, in this case the decision was made very quickly at the board's Locomotive sub-committee.

Drummond was certainly an autocrat in the Locomotive Department. Bonavia's argument that there were conflicts between the Locomotive Superintendent and other senior managers seems unfounded in the case of Drummond up to 1912. There seemed not to be one man in the company, neither director, nor manager, that felt confident enough to take him on. However 1912 was the year of changes. The directors brought in a new general manager, Herbert Ashcombe Walker, who was charged with reforming the company. It was at this point that the only case of conflict with another senior manager has been documented.

Walker tried to assert his authority over Drummond before the engineer's death in September 1912 and Urie's son remembered an early spat between them. During the 1911-12 coal strike Walker ordered some American coal without consulting Drummond. Angered by this, Drummond had a bucket of the coal brought to Waterloo and emptied the contents over Walker's officer floor. Walker however was not going to put up with this sort of insubordination, and on the death of Drummond, Urie was appointed Locomotive Engineer. Urie informed Walker that he had never expected to get the job at the age of 59. Walker told him not to worry, he was going to fire Drummond very soon anyway. After his death, obviously trying to assert his control over the Locomotive Department, on the advice of Walker, the Board made Urie Locomotive Engineer rather than Chief Mechanical engineer. In addition the role of running the trains, which for many years had been under the Chief Mechanical Engineers' Department, was transferred to the Traffic Department.

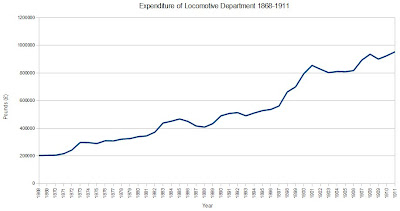

Overall there is evidence that Drummond was a typical isolated department head that got his own way and perused his own interests within the department. The way he ran his department, using large amounts of resources and at time building locomotives that were simply 'flights of fancy,' must have affected the costs that the department accrued. Table 1 clearly indicates that after 1895, the year of Drummond's appointment, the costs of running the Locomotive Department rose significantly. Of course other factors may have played a role in the increase, such as the costs required to make the department efficient or bring the locomotive stock up to the required quality given Adams' ailing last years. However, what is clear is that ever since 1868 department costs had risen at a steady rate and after 1895 there was a significant increase. Thus, Drummond's influence and independence did have a detrimental affect on overall company efficiency.

Sources:

Sources:Urie, J.C. 'Tips for aspiring CME's' South Western Circular, Vol.10 No. 9, (January, 1997) pp.221

'Dugald Drummond Obituary', The Railway Engineer, December 1912, reprinted in The South Western Circular, Vol. 8 No. 6 (April 1990), pp.145

Chacksfield, J.E. The Drummond Brothers, (Ringwood, 2005)

Jumat, 26 Februari 2010

Looking for Albinus

In my research at the National Archives the general area of research is the London and South Western Railway's (L&SWR) management between 1864 and 1914. However on April 22nd (and yes book it in your diary) I present my first ever paper at History Lab, the Institute of Historical Research's Postgraduate Seminar. The title is 'Managing the 'Royal Road': The Development and Failings of Managerial Structure on the London and South Western Railway 1836-1900.' Therefore I have had to do more research on the early period of the company's history.

We are generally under the impression the General Manager or Chief Executive were mainly an invention of the later Victorian railway companies. Yet on the 8th August 1845 the L&SWR's Resident Engineer, Albinus Martin, was appointed by the Board to take charge of the 'whole concern' of the L&SWR. WHAT!!! This made him, if not in name, the first General Manager of the L&SWR, and probably one of the earliest examples in the industry. Special lad! On reading this my brain did its irritating little habit of thinking that there must be masses of files somewhere; correspondence, letters, diaries must have survived, he must of left SOMETHING. I'll get this out of the way now, he didn't. The man died and left literally nothing. He is a historical enigma. But before I knew this fact, my compulsion to look under every stone kicked in!

First of there was the problem of the name. In Williams' three volume history of the L&SWR he names Martin, frustratingly, Albino, rather than Albinus. Secondly the documents that I looked at, including the source above, only refer to him as simply as 'Mr Martin. So therefore I went looking for more information on him, and the only thing that came up was Wikipedia, which didn't say anything. Therefore frustrated by my lack of information I searched every combination of 'Martin' and 'London and south western' that I could in Google. Google is a sobering experience when having to trawl through all the tosh! How can an estate agent have a reference to the L&SWR on its website? Don't ask me, but there it is, extending my research! After 2, or was it 3 hours, and much pounding of the keyboard, I finally came up with a biography of an 'Albinus Martin' on archive.org, which had his obituary from the journal of the Institute of Civil Engineers. Huzzah, eureka!

Now the engine was running, I could act! Next I placed a notice in the South Western Circle newsletter for any information. I got a nice letter (and it is nice to recieve an actual written letter) from a Circle member detailing Martin's life before and after working for the L&SWR. Lovely as the letter was, it only embellished a little more that which was in the ICE's obituary. So I was still nowhere. I then went back to Google and searched the correct name...after surprisingly less tosh, I found something about some signals he invented, but nothing that would really help me. Then I used the 19th Century on-line newspaper and journal archives to see if there was anything. Again after a day of searching every combination of 'London and south western' and 'Albinus Martin,' no new information came to the fore. Therefore with no archive of letters, very little information and no new leads, I hit a dead end...I'm still here after wasting what must be at least two working days.

The problem, in 'looking for Albinus,' was that I spent so much time searching for information that I failed to realise that I had all the material I needed for my work from within the company files. Therefore if there is a lesson I should learn it is that I occasionally shouldn't get carried away with flights of fancy and letting my work be led by just my curiosity about a subject or personality.

Some months after, while out for a run, I was listening lecture about Richard Trevithick's demonstrations of the first steam train in 1808. In it the lecturer said that one of his sources of evidence was a book from the 1850s. In it one Albinus Martin gave a recollection of the event having been a witness. The lecturer then said, "now I can't find much information of Albinus Martin." 'Well,' I thought, 'you're not the only one,' and kept on running...

Minggu, 14 Februari 2010

Developing the British Railway Manager

In 1830 there was no such thing as a railway manager. Of course there were people who managed railways, but there was no one in the labour market, the country, or anywhere, who had had any prior experience of running the rail. Therefore early directors, faced with some the most complex organisations that had been established in history, appointed their managers mainly from three non-railway sources. There were whose who had worked on similar businesses such as canals, engineers and gung-ho military types. In fact it was the latter that was favoured by directors. This was because the military were the only organisations where individuals coordinated more than just a smelly guy with a cart. In fact after Waterloo and the dramatic scaling down of Britain's military, there was little else for meandering ex-military men to do.

A number of studies have shown the influx of military men into the railways. Terry Gourvish, who I bet will get more than one mention in this Blog, did his PhD on Captain Mark Huish, the first General Manager of the London and North Western Railway, (L&NWR). He was late of the 67th Bengal Native Infantry (Gourvish, 1972, p.48). Michael Bonavia also noted Captain Eborall of the London and Birmingham Railway, Captain Laws and Binstead of Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) and Captian Coddington of the Caledonian Railway (CR). (Bonavia, 1971, p.13) In short, military men were everywhere.

My own PhD has however shown that no senior London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) managers that I know of did any form of military service (trust it to be different) .There was Albinus Martin, the first 'General Superintendent,' who was an engineer and helped build the company's first line between London and Southampton. There was also the scallywag, Cornelius Stovin, who was a failed stagecoach proprietor and in 1852 saw fit to run off to the United States, taking some cash with him (never to be seen again). What this shows is that while in some respects some early railway managers were trained professionals in other fields, especially the engineers, in general they were a mixed bag of individ uals who directors were forced to employ because their was no other option.

uals who directors were forced to employ because their was no other option.

By the end of the 19th century a dramatic change had occurred. In 1898 the London and South Western appointed their third General Manager, Charles Owens (Shown). He was the personification of the late-Victorian career railwayman. He had started with the company in 1862 at the age of 16 as an apprentice Clerk in the Audit Office. He had moved gradually through the ranks to clerk, chief clerk and then Goods Manager in 1888. 10 years later he was appointed General Manager of the company, a post he would hold until 31st December 1911. What Owens' career demonstrates is that the nature of the railway manager had changed dramatically. No longer were directors appointing a misfit bunch of individuals to run their operations, now they had a they plethora of long-standing and experienced railway employees who knew the lay of the land.

Evidence from my PhD therefore shows a change in the age at which managers started with the L&SWR. Of twenty eight L&SWR managers that began their careers in the period 1839 to 1859, 42.8% started between the ages of 20 and 60 and therefore must have worked in other businesses. Indeed its seems that before 1870 the L&SWR did a fair amount of poaching railway talent from companies allied to their business. However in the period 1860 to 1879 only 11.7% of 34 managers began their careers after the age of 20 and after 1880 none did. Boring as these statistics are they do show that management was increasingly being populated by individuals who had started with the railway in their teenage years and thus had had their entire career within the industry. Further to this all the managers had careers on the clerical promotional ladder, moving from junior (or apprentice) clerks, to clerks, then chief clerks or station masters and then being appointed to middle management. Overall only 3 out of a sample of 70 managers started with the L&SWR in non-clerical positions such as porters, inspectors or ticket collectors. Therefore it can also be said that the majority of managers had only followed one type of career path.

Therefore there is a binary character to railway management in the late Victorian period. On the one hand you had senior and middle managers who knew the ropes of the railway industry well, had vast experience and had worked their way up from the bottom. The problems of recruitment in the earlier period had been dispelled as no longer were directors forced to search outside the industry for managers who were hard to find and whose trustworthiness could not be assured. On the other hand however most managers in the later period only had experience of one industry and one career path, which may have led to managerial institutionalisation. In an effort to solve the problems of early managerial recruitment by favouring internal appointments, it is possible that directors and senior management created an environment where innovation and new ideas were uncommon as no 'new blood' was entering the railway industry. This subsequently may have affected the performance of Britain's railway companies in the late Victorian period.

However that is a question for another post...

FURTHER READING:

Bonavia, Michael R., The Organisation of British Railways, (Shepperton, 1971)

Gourvish, T.R., Mark Huish and the London & North Western Railway: A Study of Management, (Leicester, 1972)